Hampshire House

The Hampshire House is a 37-story cooperative apartment and hotel building, located at 150 Central Park South in Manhattan, between Sixth Avenue and Seventh Avenue, opposite Central Park. It contains 155 apartments, spa, health club and other utilities.

The Hampshire House was built on part of the site of the old Navarro Flats, demolished in 1926. The original plan was an addition to the Hotel Maurice on West 58th Street, designed by Caughey & Evans in 1926. It would be the 39-story building called Medici Tower, with a dome aloft on a tall shaft.

By 1930, H.K Ferguson Company of Cleveland, Ohio, was the new owner and joined with Eugene E. Lignante in planning the building. Architects Caughey and Evans designed a new plan for a 36-story apartment hotel, initially called Central Park Suites. Prior to October 5, 1930, the firm Sutton, Blagden & Lynch was appointed as agents, according to the New York Time.

Edward L. Bernays (1891-1995) worked at the construction firm Merritt-Chapman and Scott and wrote (Biography of an Idea: Memoirs of Public Relations Counsel, 1965):

«Hampshire House lay fallow for seven years and then blossomed again.»...

«In November 1930 Katherine Seaman, pioneer woman realtor associated with the firm of Sutton, Blagden and Lynch, developed a vague plan for an apartment hotel, envisaged by her as the most modern, luxurious establishment ever built in a residential section. "Will you make my dream come true?" she asked.

Her assignment appealed to me, for she wanted me to use all my initiative in planning the establishment. "Stretch your imagination to the limit," she said, "to make this absolutely the last word in apartment-hotel living." The structure was to be built, she said, on Central Park South between Sixth and Seventh avenues, on the site of the famous old Spanish Flats, New York's first luxury apartment. In 1930 a woman or man with a big idea could still find other people's money. Miss Seaman asked me to a conference of her team to complete the deal. An insurance company representative agreed to finance her purchase of the property and the construction of the thirty-seven-story building, at a cost of $6,000,000. The huge structure quickly began to rise, the latest addition to a new skyline for Central Park South. One apartment included the largest single room ever built into a private suite, 45 feet long by 22 feet wide and 18 feet high. And two penthouses topped off Hampshire House, each three stories high, the top floor of each a complete living unit.

The new Hampshire House Corporation engaged us for a year for $5,000 in cash and $5,000 in preferred stock of the owner corporation. I was of course speculating in accepting preferred stock. But I welcomed the opportunity of applying public relations at the inception of a project, instead of waiting until it had crystallized.

The name of the new residence, I thought, was an important element in its acceptance by the public. That meant we would have to find a name for the project. Should we call it Malmaison, Trianon, Elysée and suggest French raffinement, or name it after an English county or English nobility— Argyll, Surrey, Essex, Wessex, Devon, Hampshire, or what? I had a decided preference for a British name. A French name did not have the ring of solidity, distinction and fashion which were associated with an English name. We chose Hampshire House. I recommended a list of innovations— a children's room, first-aid room, radio room, library, photographic development room, reading room stocked with domestic and foreign newspapers, and an English breakfast room. I suggested a resident governess, a masseur, polite porters and doormen and neatly uniformed page boys. I planned a specially wrapped soap for the guests, a new idea then, centrally controlled electric clocks for each apartment and engraved letter paper.

Encouraged by Katherine, I wrote to Griffin's, the shoe-polish manufacturers, about the installation of an ultramodern ladies' shoe-shine parlor; to De Zemler's Barber Shop about his taking over the men's barbershop concession; to the Hotaling News Agency about a newspaper room; to Faber, Coe and Gregg about a lobby cigar stand; to Johnson and Johnson about installation of a complete firstaid room; to Eastman Kodak Company about equipping a photographic development room; and to the New York Edison Company about an English-style breakfast room equipped with the latest electrical gadgets. And I wrote to Studd and Millington Limited of Bond Street, uniform outfitters in London, for estimates on designing and tailoring uniforms in the authentic English tradition for the hotel attendants. Also we wrote to a thousand men and women in the Social Register to ask for suggestion for the book titles to be included in our proposed library.

I suggested to Miss Seaman that we stamp the project with the mark of English gentility by associating badminton, a game still new to America, with it. The apartment hotel would become the headquarters for information about the game.

A cornerstone ceremony, I believed, was a necessity−a ceremony to symbolize the establishment and demonstrate its character to prospective tenants. We gave ourselves six months for the job.

I thought an illustrious Englishman would add distinction. The Marquis of Winchester bore the highest title in Hampshire county. We failed to bring him to New York. But we used the Winchester coat of arms on the ornamental metal work, folders and writing paper. In January 1931 I cabled Sidney Walton, the London publicist, to find an English nobleman to lay the cornerstone, and later to act as Hampshire House host. Walton submitted names of impecunious peers, but their fee was too high and we abandoned the idea.

Three themes dominated the ceremony: modernism, the English influence and the historical site. I envisaged headlines that read, "Modem Apartment Hotel on Site of New York's Oldest Flats".»

«We included in the cornerstone: A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway, Peter Ibbetson by George du Maurier, Skyscrapers by John Alden Carpenter, Strange Interlude by Eugene O'Neill, Thomas Hart Benton's reproductions of murals "America Today" in the New School for Social Research, a photograph of the new Packard automobile, John Brown's Body by Stephen Vincent Benét, a reproduction of "Mother and Child" by Zorach, and a reproduction of an Autogiro. For good measure we added Old English Mansions by Charles Holmes, Valentine's Manual, The New Yorker Album and New York newspapers of March 24, 1931, including a rag-paper copy of the New York Times, with photographs and a historical record of the site.

[...] about forty guests attended the ceremony.

The builders, eager to finish the building, did not stop work for the ceremony. The sound of riveting hammers disturbed the festivities. A Mr. Villaume, builder of the original Spanish Flats, discoursed on the old site and the new building. An official British representative discussed "hands across the sea." Harry Alan Jacobs, architect, acted as chairman. Cables came from Viscount Lymington, member of the British Parliament for Hampshire County, and Sir Thomas Inskip, Recorder of Kingston upon Thames, stressing the British-American entente. The Lord Mayor of Portsmouth, England, J. S. Smith, sent a cable of good will. Gerald Campbell, British Consul General, sent greetings.»

«But Hampshire House was stillborn. Due to money stringency, the company financing the construction refused to make further advances. Requisition of funds by the contractors could not be met, and work was stopped on July 15, with the building completed except for the interiors. A meeting of corporation creditors was called within a few days. Everything stopped. The Hampshire House corporation went bankrupt. For seven years this lovely unfinished building, a beautiful monument to modernity, to yesterday's charm and tomorrow's convenience, stood battered by wind, snow and rain, a dead symbol of the Depression. Then, in 1938, seven years later, a new organization took over the old corporation. I had no connection with it. Hampshire House was revived in all its glory.»

Construction of the Hampshire House began in January, 1931, cornerstone was laid in March and the unfinished building was abandoned in July 15, about 75% completed and roofed over, but not closed. It was times of Great Depression.

In August, 1937, two exhibition apartments in the Hampshire House, with one and two rooms, were open for inspection. Douglas L. Elliman & Co. were the agents for the building. Caughey & Evans, the architects, were hired to complete the building. It was finished in 1938 in Art-Deco style, with copper roof and two tall chimneys. It was initially a rental apartment building.

The Kirkeby Hotels acquired the Hampshire House in 1946. The group also controlled the Sherry-Netherland Hotel, the Gotham, and later merged with Hilton. Hampshire House was converted into a cooperative in 1949, with 220 apartments.

|

Copyright © Geographic Guide - Historic Buildings in NYC. |

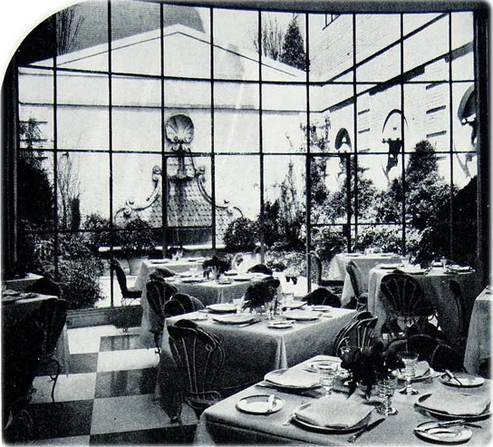

A view in the Fountain Room at Hampshire House. An advertising in 1946 by the Kirkeby Hotels.

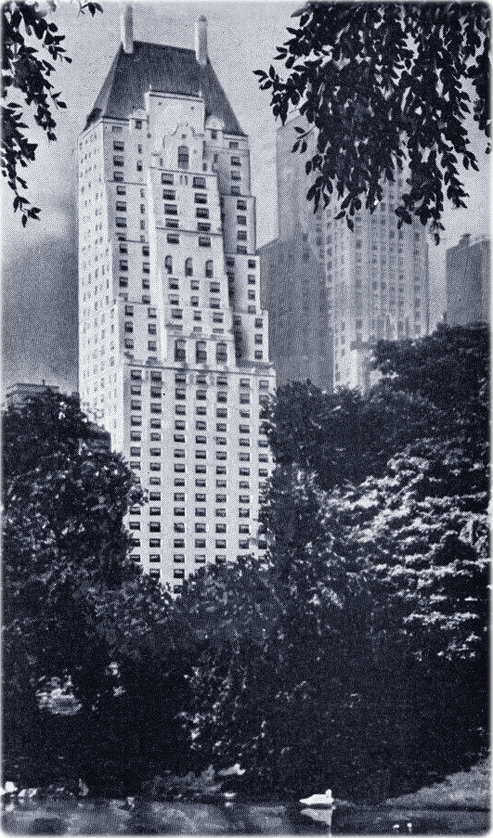

Hampshire House in a vintage postcard by East and West Publishing Co.

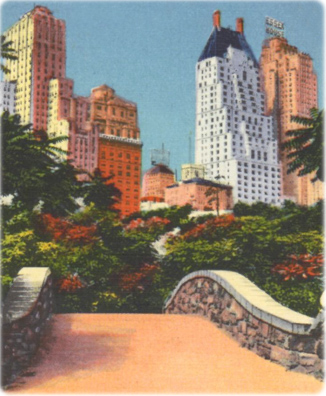

Central Park South, with Hampshire House under construction on May 1, 1931. Photo from the NYPL.

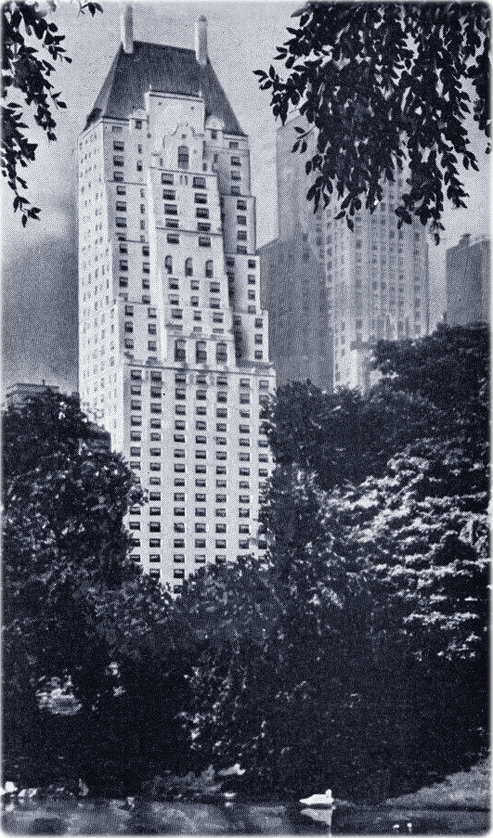

The Little Bridge in Central Park, looking towards Central Park South, with Hampshire House and the adjacent Essex House in the background. Vintage postcard Landmarks of New York City with seal of the City of New York.

Hampshire House