New-York Theatre, first Park Theatre

The New-York Theatre was built from 1795 to 1798, facing Chatham Street (now 21–25 Park Row), New York City (before 1807 the exterior was still considered unfinished). The Theatre was destroyed by fire in 1820 and replaced by the "second" Park Theatre. This was the first Park Theatre, although the New-York Theatre was not officially referred to by that name. In its early years, it was officially called the "New Theatre" and later simply the "Theatre". Outside New York, it was called the New-York Theatre. Local newspapers began to call it "Park Theatre" by 1799. Four independent contemporary illustrations of its fronting are known, made by artists C. Milbourne, A. Robertson, E. Tisdale and J. Holland, and scant further descriptions of its external design, although there are rich descriptions of its interior. The rear on what is now Theatre Alley is shown in the Saint-Mémin view of 1798.

In the late 18th century, New York was the largest city of the United States. The city's growth and the New York elite required a theater that was on par with the European theaters. At the time, New York's only playhouse was the decaying John Street Theatre. It opened in 1767 and was called the Royal Theatre during the British occupation of New York until 1783. After that, the name changed to "New York Theatre". It closed after the last performance on Saturday, January 13, 1798: the comedy The Comet by William Milns, days before the opening of the "New Theatre".

The New Theatre was designed in 1793 in a rather impotent neoclassical style by French architect Marc Brunel, who won an architectural contest to design the Theater. Marc Isambard Brunel (1769-1849) arrived in New York in 1793 and was appointed Chief Engineer of the City, in 1796, after taking U.S. citizenship. He left New York in 1799 and, later, became famous for the construction of the Thames Tunnel, in London, built between 1825 and 1843.

On July 8, 1794, the following message was read in The Daily Advertiser: "The committee appointed to report on the most eligible situation for erecting a new Theatre request the favour of all those gentlemen who have already subscribed, also those who wish to become subscribers, to attend this Evening, 8 o’clock at the Tontine Coffee House". In October, Lewis Hallam and John Hodgkinson met with investors. Initially, there were 115 subscribers, who purchased 113 shares in the venture. In the meeting, Jacob Morton, Carlile Pollock and William Henderson were appointed the trustees.

The site was chosen on the east side of Chatham Street (now Park Row), facing the Fields or the Common (now City Hall Park, the City Hall was still on Wall Street), about 200 feet north of present Ann Street and backing on the Mews (now Theatre Alley, see a 18th century map). It was a kind of northern end of the urban area. The site was formerly known as the "Vineyards" or the "Governor's Garden". The entire block was granted to Ann White in 1786. The site (lots 6, 7 and 8, now numbered 21, 23 and 25) was 78 feet along Chatham Street, 130 feet to the Mews, 85 feet along the Mews and 165 feet on the west side.

The cornerstone for the New-York Theatre was laid on May 5, 1795. The commissioners were Jacob Morton, William Henderson (acting agent for the committee of proprietors) and Carlile Pollock. A petition for extending the portico of the Theatre across the foot walk was rejected by the Common Council on June 1, 1795. Brunel became Chief Engineer of New York in 1796 and the construction of the Theatre was supervised by French architect Joseph-François Mangin (1758-1818) and his brother Charles. Later, J. Mangin became city surveyor, designed the new City Hall and the Saint Patrick’s old Cathedral.

The New-York Theatre was roofed by September, 1796. It was one of the most imposing buildings ever constructed in New York up to that time. The costs more than tripled and more shares were sold. They also borrowed more money from investors, from the Bank of New York and from the Branch Bank of the United States in the City of New York. By 1797, there were 130 investors in total. Edward Livingstone became an additional trustee. The managers were originally Lewis Hallem Jr. (c.1740-1808) and John Hodgkinson (1766-1805), members of the John Street Theatre company. In a meeting on May 25, 1797, it was decided that William Dunlap, also from John Street Theatre, and John Hodgkinson should become joint lessees of the New Theatre. Both were also managers of the Old American Company. An arrangement was reached between Henderson, Dunlap and Hodgkinson in which they agreed to four playing seasons, to commence the ensuing autumn, once the house was ready for exhibitions.

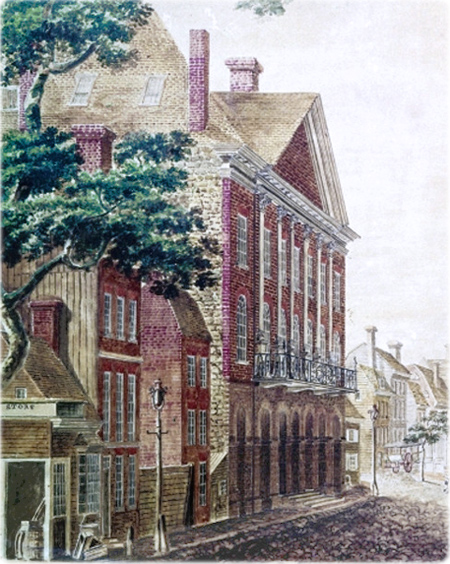

The external design of the building, in the Greek revival style, was not erected exactly as shown in the Longworth's City Directory for 1797. The entrance was by a flight of five or six steps, which, according to the Tisdale's engraving, extended the whole length of the structure, but Milbourne and Holland represented it as the width of the five central doorways. The eagle frieze at the top of the façade (not shown in the Milbourne painting on the right), representing a national emblem (similar to the emblem at the Federal Hall), was never built and there were differences in the ironwork on the balcony. Tisdale shows ten Corinthian columns, but only six were built as depicted by Milbourne. Holland depicted six Ionic columns and a round window on the pediment, which could have been added during the 1807 renovation. There were seven arched doorways and above them were two stories of windows, surmounted by a pediment. The annex to the left side, at the back, was used for rehearsals, green room and other rooms for the actors. The stage entrance was from the Mews (Theatre Alley).

On January 23, 1798, the opening of the New-York Theatre was announced in the Commercial Advertiser for Monday, January 29, as "New Theatre", still under construction. Doors would open at 5 and curtains drawn up a quarter past 6 o'clock. Ladies and gentlemen were requested to be particular in lending servants early to keep boxes. There would be an office for the sale of box and pit, and another for the gallery tickets. Two attractions were announced for the opening: Shakespeare's comedy As you Like it and the musical the Purse, or American Tar, which seems to be a John Hodgkinson's adaptation of the musical drama The Purse; or, Benevolent Tar by J.C. Cross, performed at the Theatre Royal, London, in 1794. The Shakespeare's comedy was performed with Hodgkinson as Jacques, Hallam as Touchstone and Mrs. Johnson as Rosalind. An occasional address was spoken by Hodgkinson and a prelude written by Mr. Milne, called All in a Bustle, or, the New House, was played.

This historic playhouse was built to contain about 2,000 persons (seats were backless benches). The interior was elegant and vast, compared to the older one. There were seven arched doorways on Chatham Street. Three of them led to the vestibule, where there were three entrances: the central one led into the boxes and the others to the managers' office and to the ticket room (charges: boxes, one dollar, pit fifty cents, gallery, twenty-five cents). On the first tier there was a spacious saloon for refreshments, lighted by three chandeliers suspended from the ceiling. In cold weather two blazing fires were kept up at either end of the lobbies.

The gallery was accessed by a narrow, spiral staircase of rustic construction. The auditorium consisted of a commodious pit, three tiers of boxes, disposed in semi-circular rows, from one side to the other of the stage, and the gallery. The dome, not visible from the outside, was decorated with allegorical subjects. The illumination was by oil lamps. In case of fire, there were three communications from the boxes with the street and two from the pit. There was a large box occupying the front of the second tier, with capacity for more than two hundred people, called "the Shakespeare".

The second night was on January 31 and Shakespeare opened the performances followed by The School for Scandal by the Irish Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751-1816). This comedy was first performed in New York in 1785 at the John Street Theatre. The third night was on February 2nd and the diminishing returns ($1232, on the first night, $512, second night and $265 third night) sounded alarm bells for the managers. The succeeding week averaged $333 a night. By the late February, after spending the original money subscribed, a debt was incurred of $85,000. July 2nd was the last night of the first season.

During the summer of 1798, decorators worked under the direction of Charles Ciceri to finish the original plans for the interior of the Theatre. Ciceri was the scenery, machinery and stage manager. He was also the scene painter. Landscapes were painted by Audin, his assistant.

The opening of the next season was planned to begin in September or October, but an outbreak of yellow fever prevented the Theatre to open before December 3rd, when were performed The School for Scandal and High Life Below Stairs. The theatre offered performances three or four days a week. In the summer, performances were suspended on account of the heat.

The American and Daily Advertiser called the new venue as "Park Theatre" in July, 1799. The New-York Evening Post, which began publication in 1801, call it "Park Theatre" in 1802, but the name in the official theatrical programming, published in the same newspaper, was "Theatre".

By 1803, artists John Wesley Jarvis (1780-1840) and Joseph Wood (c.1778-1830) had their studios on the first tier until about 1810. In December 1804/ January 1805, an exhibition of paintings was open every day at the Theatre, except Sundays.

In the early 19th century Dunlap became the sole proprietor of the Theatre. Unfortunately, it was not making enough money to pay the bills. Dunlap declared bankruptcy and the property was auctioned off at the Tontine Coffee House, on February 10, 1804. It was bought by a company of 31 men, including McCormick, Waddington, Coles, McVicker and Shaw. At the time, the Evening Post reported that the Theatre was still in unfinished state. On February 22, 1805, the Theatre was temporally closed and Dunlap retired as manager. The theater opened on March 4, under the direction of Johnson and Tyler. The new owners sold theater to John Jacob Astor and John K. Beekman on April 21, 1806.

In 1807, from about May to August, the theatre's interior was completely remodeled under the supervision of John Joseph Holland (1776-1820), a British architect and scene painter who emigrated to the United States in 1796. The auditorium, from the pit to the dome, was pulled down, a new pit was erected both wide and deep. In the front of the house there were two large rooms, one over the other. The lower of which was intended as a tea and coffee room for ladies and the upper as a sort of bar room for gentlemen. Four new tiers of boxes replaced the previous three tiers and the "Shakespeare box" was gone. The walls were repainted. The ceiling was painted with panels of a light purple and gold moldings, with a balustrade and sky in the center. There was a crimson curtain over each box. The lower boxes were lighted by ten glass chandeliers. There were a large oval mirror at the end of the stage boxes.

In 1808, Stephen Price (1782-1840), a lawyer in New York, became the manager. By 1810, he was assisted by Edmund Simpson (1784-1848) as stage and operating manager. The New-York Theatre was at its peak in terms of quality of dramatic performances and intellectual interest. The English actor George Frederick Cooke (1756-1812) appeared here, for the first time in the United States, on November 21, 1810, as Richard III. Cooke died in September, the next year, in New York. A monument to his memory was erected in St. Paul's Chapel.

During the summer of 1811, the interior of the Theatre was again painted, the lobbies were remodeled to provide more comfort for ladies and the lighting was rearranged. In December, two new doors were made to connect the boxes to the street in case of accident or fire (making a total of six). In November, 1813, Russian stoves were installed to heat the premises. In the recess of 1816, the theatre was again redecorated. From 1811 through 1820, painters John Evers, Jr. (1797–1884), born in Long Island, and Hugh Reinagle (1790–1834) from Philadelphia, worked for Holland at the Park Theater and were both his apprentices. Evers and Reinagle were two of the founders of the National Academy of Design in 1825. Reinagle was the architect of the second Park Theatre.

In the early 1820, Park Theatre was in difficulty was closed. It reopened on February 22 on Washington's birthday night.

The Theatre was destroyed by fire on May 25, 1820, after a performance of the drama "The Siege of Tripoli" in which firearms and powder were used in abundance. The fire was discovered by one o'clock, later that night, when the crowded audience had already dispersed. Within a few hours, nothing remained but walls.

The origin of the fire was not discovered but it started near the ridge of the southeast corner of the roof, and it was believed it was not caused by the fireworks employed in the course of the entertainments of the early evening. It was believed it was caused by an accident or negligence. There was no insurance on the building, but a partial one on the scenery or other property. More than 200 people were connected to the establishment, including mechanics and laborers.

The managers of the Theatre immediately engaged the Anthony-Street Theatre (now Worth Street) and, on the 29th of May, four days after the calamity, the Stephen Price's theater company performed there.

The owners John Jacob Astor and John K. Beekman began to rebuild the theater in January, 1821, but with a much simpler façade. The new Park Theatre reopened on September 1, the same year.

Jonildo Bacelar, Geographic Guide editor, March 2025.

The Theatre at New York penny token, probably issued in 1797 or 1798. It is a large 34 mm or 35 mm undated copper piece with a weight range of 402.8 to 409.8 grains. It bears the die maker's signature "Jacobs" (possibly Benjamin Jacob of England) below the stairs. There are only 13 known pieces of it. The engraving is probably a simplified version of the view of the "New Theatre" drawn by Tisdale about 1797 (see above).

Façade of the New-York Theatre by architect J. Holland, about 1807. Here the six Corinthian columns were replaced by Ionic ones.

Fragment of the View of New York from Brooklyn Heights in 1798 by Saint-Mémin, showing the East River waterfront, the North Dutch Church (right) on William Street and the rear of the New-York Theatre on the Mews (now Theatre Alley). See a similar view before the construction of the Theatre in the 1796 Taylor-Roberts view.

The "New Theatre" by Tisdale, as published on the Longworth's City Directory for 1797. Engraving based on the drawing above.

Tisdale's New York Theatre on Chatham Row (now Park Row), in neoclassical style with ten Corinthian columns, about 1797.

The New York Theatre on Park Row in 1798, watercolor by Charles Cotton Milbourne.

New-York Theatre, first Park Theatre

|

Copyright © Geographic Guide - Old NYC. Historic Theaters. |